Welcome to the 16 awesome new readers who joined in the past week!

If you haven’t subscribed, join 2,489 smart, curious people interested in Changing Greece.

Note: This newsletter post is an investigation into the state of Greek salaries in 2024. It is a compilation of latest data on salaried employment in the country across a range of sources, metrics and timeframes.

💶 Salaries in Greece (2024 Edition)

There are many ways to look at the state of salaries in a country.

You can look at gross salaries, real wages, labour costs, average annual income, etc.

Journalists and politicians usually cite one metric over the other, depending on their narrative and what does the least/most damage to them/opponents.

They also focus on specific periods of time, often in the short term, disregarding the macro picture and longer term trends that play an important role.

Single charts and snapshots might be great for viral headlines (good or bad), but they can never tell the full story.

This article is about the story of Greece’s salaries. The story is a slightly colorful one, with a lot of black and some white.

At the end of the day, it’s mostly fifty shades of dark grey.

How much do Greeks earn?

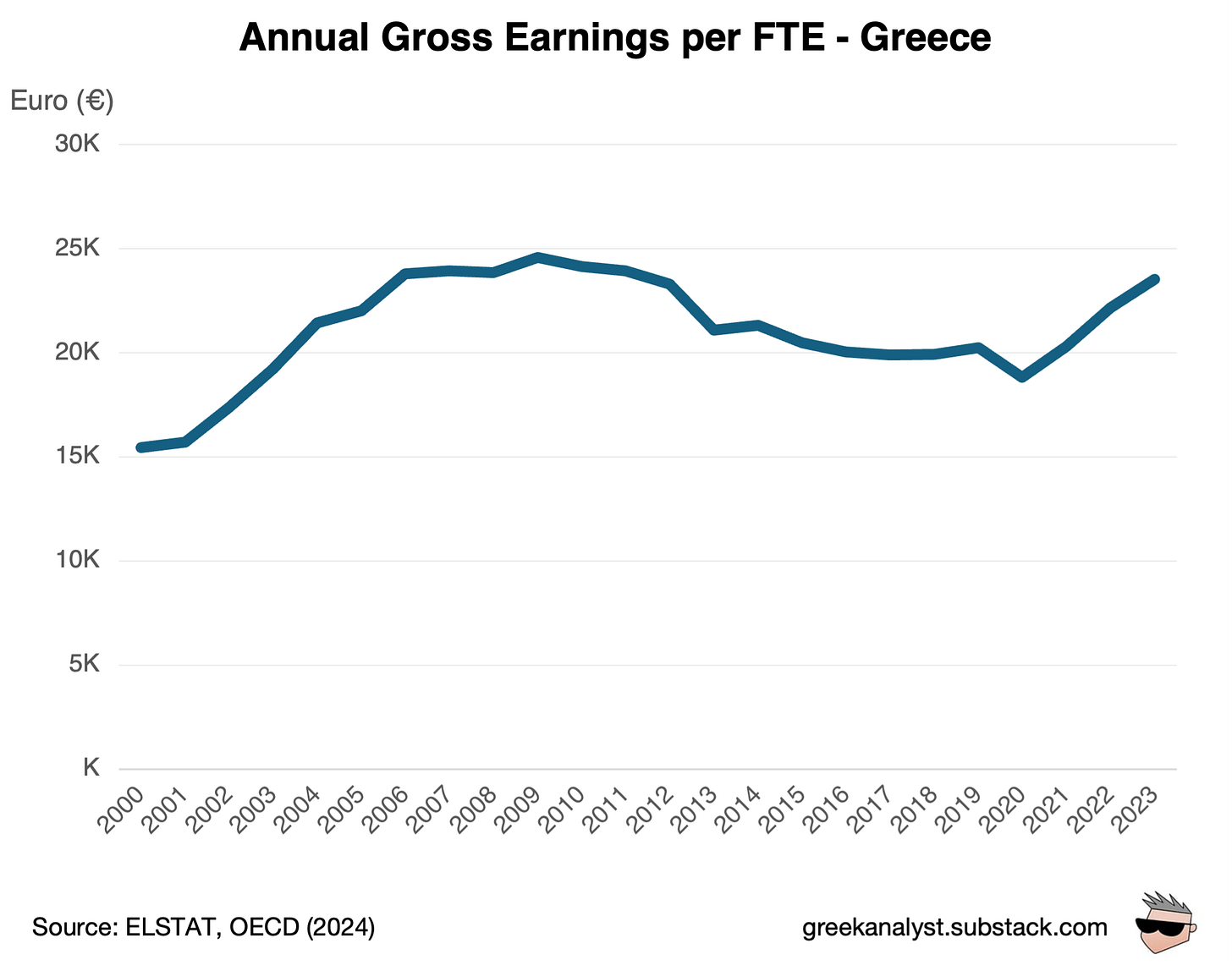

Let’s start by looking at gross earnings — i.e., income earned before any deductions, such as taxes and social security contributions.

Annual gross earnings per Full-Time Employee (FTE) rose steadily since 2000 and kept going down for more than a decade after the Greek crisis erupted.

2020-2023 was the first four-year period of consistent positive growth since 2007.

We are now very close to the pre-crisis peak of 2007.

That looks like a decent recovery, right? Well, not quite.

If we compare gross earnings in Greece with the OECD average, we see that Greece has consistently underperformed since 2009.

The gap with the OECD average kept growing until 2020. It remains large today but Greece has picked up the pace and is trying to close it over the past few years.

What about net earnings?

In terms of annual net earnings, Greece remains below the EU/EZ average but close to the median (enjoying a higher position than 12 other Member States).

Salaries in the Greek private sector

Let’s now turn to the Greek private sector.

The average gross monthly salary in Greece’s private sector has increased from $1,042 in 2014 to $1,251 in 2023. That’s about a 20% increase. Not bad (but remember, this is still the gross amount).

Not everyone receives the same amount of salary. So, who earns what?

Here is a good list of salaries across different occupational groups. And here is a deep-dive I did a few months ago on tech salaries specifically.

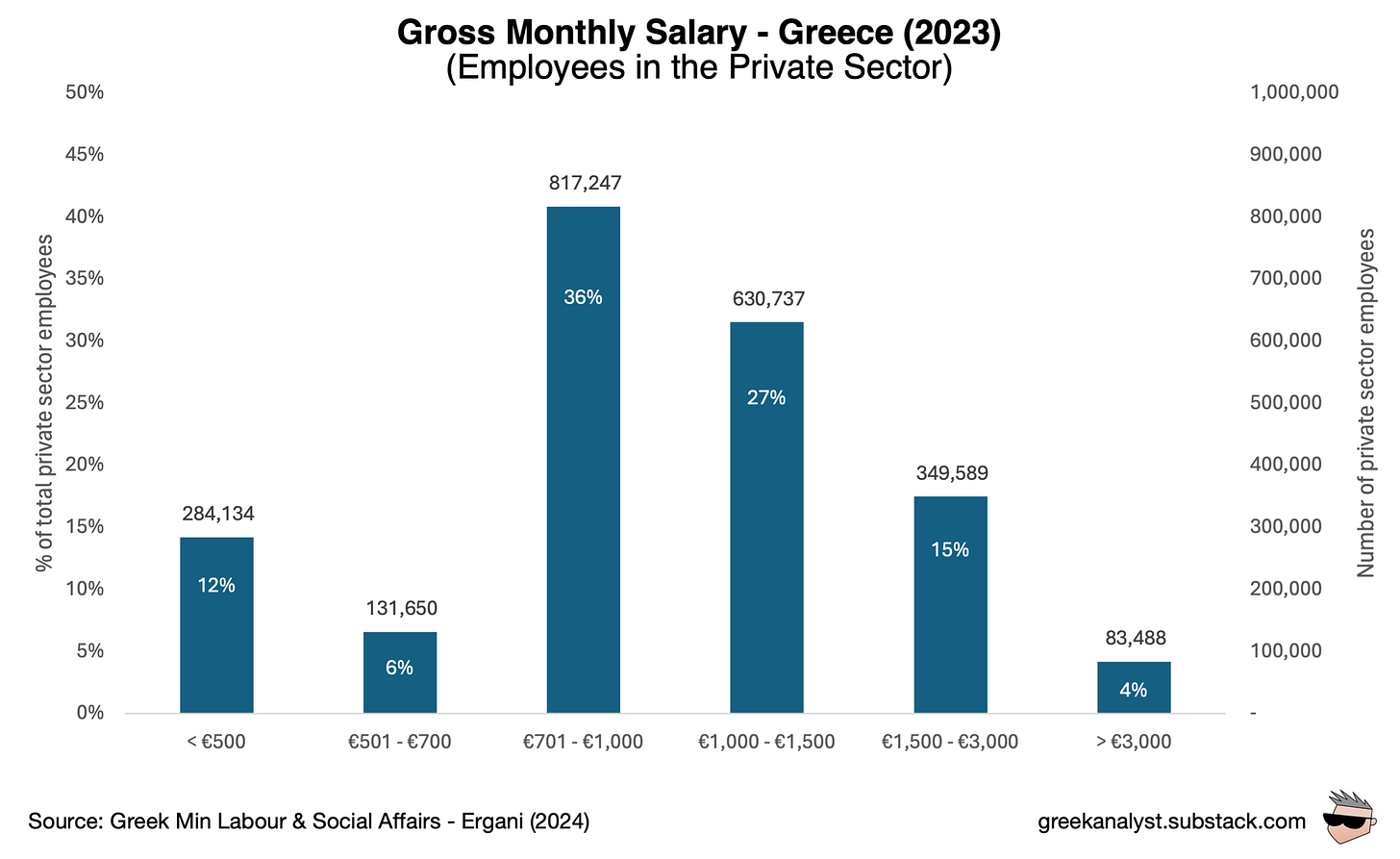

We can also look at the distribution of Greece’s 2.3 million private sector employees between different salary levels.

More than 54% of private sector employees earned less than €1,000 per month in 2023 (down from 63% in 2015).

Close to 43% earned between $1,000 and $3,000 per month (up from 34% in 2015).

Only 4% earned more than €3,000 per month (slightly up from 3% in 2015).

The numbers are certainly improving, but Greece still has a long way to go.

Salaries in the Greek public sector

The Greek public sector has different salary bands depending on the level of education attained by the worker. It also offers a number of extra subsidies.

Here is an example of the public sector salary band for university graduates.

There is extra support for parents and people with disabilities. Having higher education degrees (Masters and PhD) bumps you up the experience ladder.

Different types of public sector professions (e.g. university professors, military personnel, judicial officials) have different salary bands and subsidies.

In a recent study conducted by the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT), the average salary of the Greek public sector in 2022 remained higher than the average salary of the Greek private sector.

How much do Greeks real-ly make?

Let’s now look at numbers in real terms (i.e. accounting for inflation).

Why is this important? Because if the annual increase in wages is not as high as the rate of inflation, then the purchasing power of one’s salary will actually be lower.

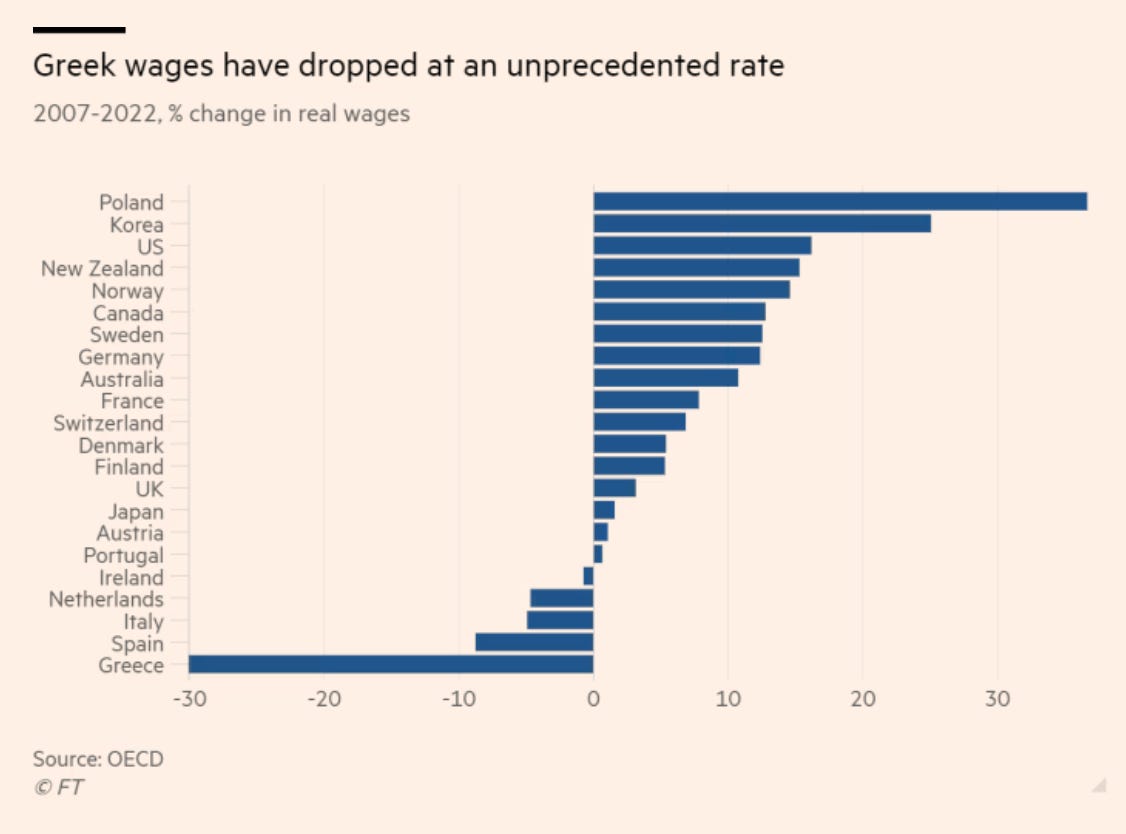

You might have seen this chart from the Financial Times.

Looks pretty bad, right? That’s because it is.

Greek workers saw a deep cut in their average annual wages due to the crisis.

But the chart is a bit misleading.

Any chart using the pre-crisis top as the starting point is not a fair depiction of reality. The pre-crisis top represents the peak of Greece’s profligacy era and the beginning of the greatest depression on record.

Anything coming after 2007/2008 will de facto be worse than what was before.

Let’s have a look at the same data as the FT chart but from two different vantage points: the periods 2007-2023 (used by the FT) and 1995-2023 (a longer time-frame).

The 2007-2023 period was grim. The average real annual wage of Greece (in USD, PPP, constant prices) had dropped 20% by 2013 and another 5% over the next 10 years.

If we zoom out, we see that Greece has had an average annual wage below the OECD average since 1995. And yet, its rate of increase was significantly higher until 2009.

That’s pretty impressive. Right? Well…

Greece’s pre-crisis high rate of annual wage growth was based on false pretenses.

Constant borrowing on a national level, extremely high public sector salaries handed out to partisan ‘clients’ by the Greek political system, as well as various other terrible habits created an unequivocal recipe for disaster.

The pre-crisis top was an “artificial” one. And it created a house of cards.

Now, there is another chart you might have seen from the Financial Times.

Pretty damning too, right? Yes, but… that’s another chart using the pre-crisis top as a starting point. As we discussed, this is a big no-no.

Let’s try to put things into context.

If we look at the same sample of countries since 1995, we see that Greece was second from the bottom. We did drop to the last place over time, but our position was pretty terrible to begin with.

If we look closer at the actual change in real annual wages, we see that while Greece had the largest drop between 2007 and 2023, it nevertheless did considerably better if we look at the wider period starting in 1995.

This is definitely not a cause of celebration. In both cases, Greece is below the OECD average (and in the latter period, last by a mile). But despite the decade-long crisis in Greece, the net difference over the past 30 years remains positive.

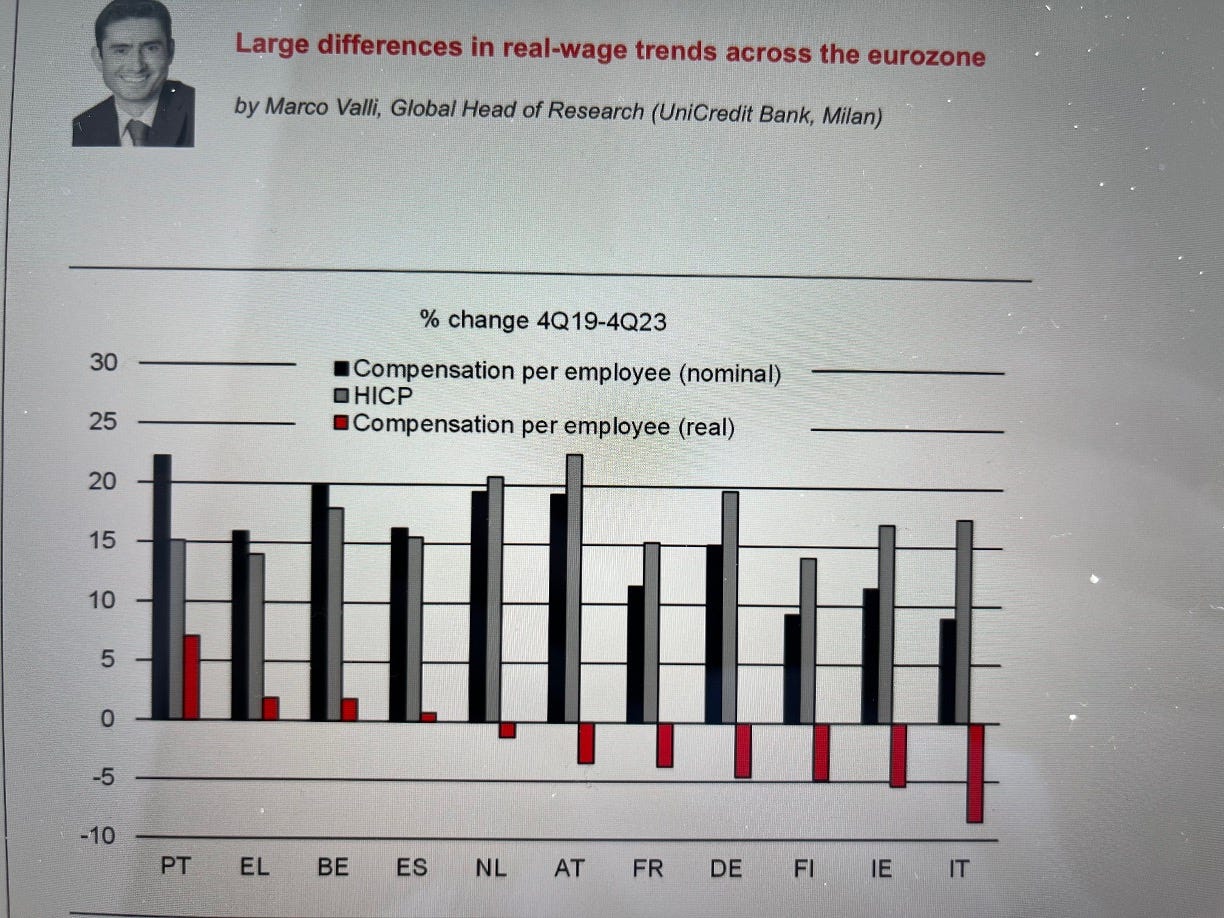

In fact, since 2019 the change in real compensation per Greek employee has not only been positive but also one of the highest across the Eurozone.

Greece will need to attain a much higher rate of increase (in real terms) to catch up with any of its EU/EZ or OECD peers, but that’s definitely a good start.

Minimum wage going up

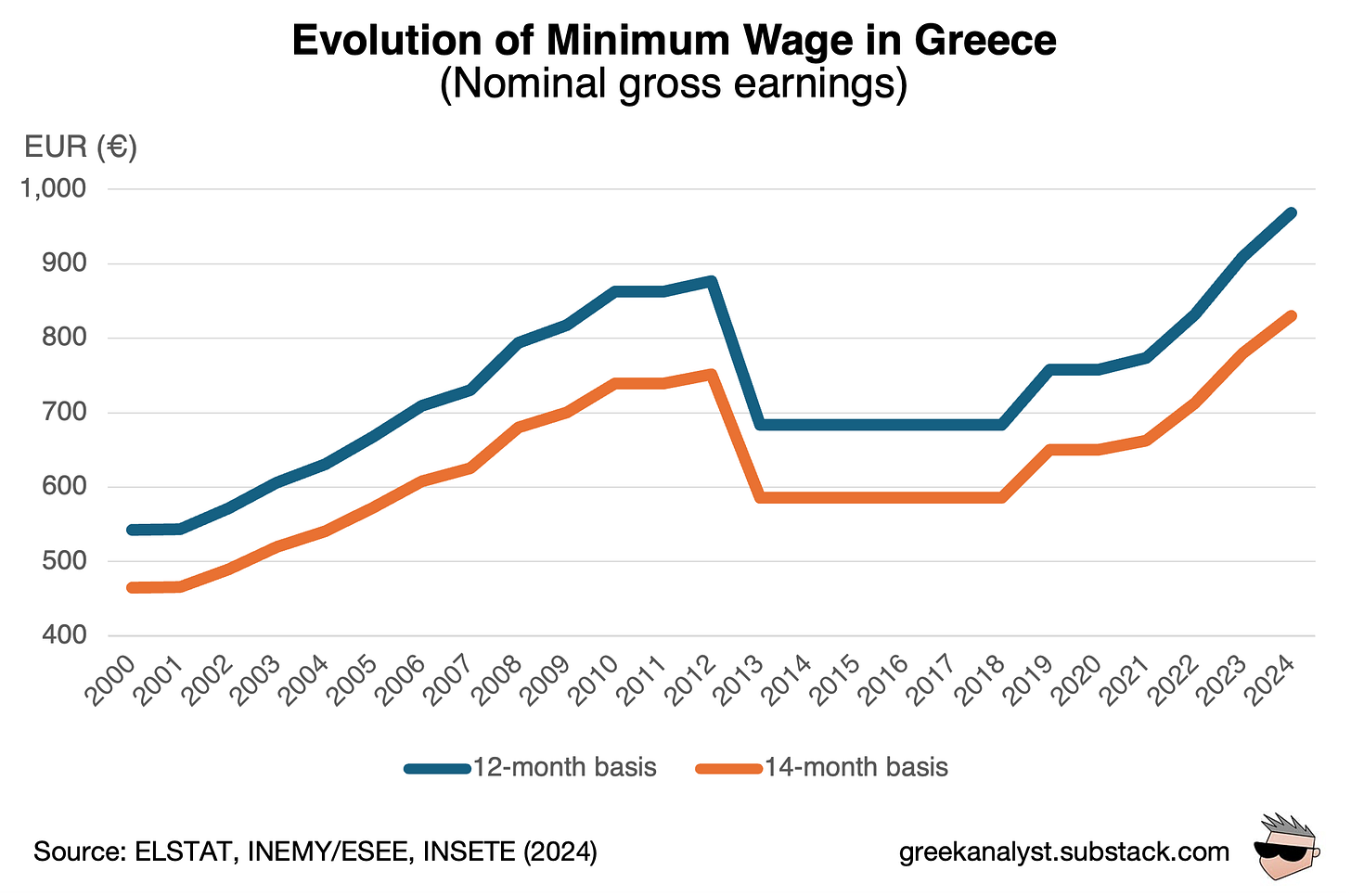

Another important dimension in terms of salary dynamics is the minimum wage — i.e., the lowest wage that an employer is allowed to pay an employee by law.

The minimum wage in Greece has changed a lot over the past 25 years.

Note: You might notice that the above chart has both a 12-month and 14-month basis for the minimum wage. If you work in Greece, you probably know why: Greek labour law mandates the payment of two extra salaries per year: at Christmas (full month salary), at Easter (half month) and at the employee's annual holiday (half month).

Rising steadily to €751 until 2012, the Greek minimum wage fell sharply to €586 for six long years, only to start increasing in 2019 (even faster than before!) until today.

In 2024, Greece’s minimum wage stands at €830 per month.

How does the Greek minimum wage compare to the rest of Europe?

It’s not too bad, actually.

Measured based on Purchasing Power Standard (PPS) units per month, the Greek minimum wage is in the upper middle section of the European distribution.

What about measured in real terms?

The real minimum wage (at constant prices) in Greece started rising sharply in 2018 but saw a decline between 2020 and 2022 due to very high inflationary pressures.

2020-2022 was a tough period with very high inflation for Greece.

Thankfully, things have gradually started to look better since 2023.

Greece’s minimum wage has increased 10% in real terms since 2019.

This increase ranks pretty well against other OECD countries, many of which also experienced high inflation over the past 5 years.

Overall, Greece’s minimum wage increase is both real and meaningful.

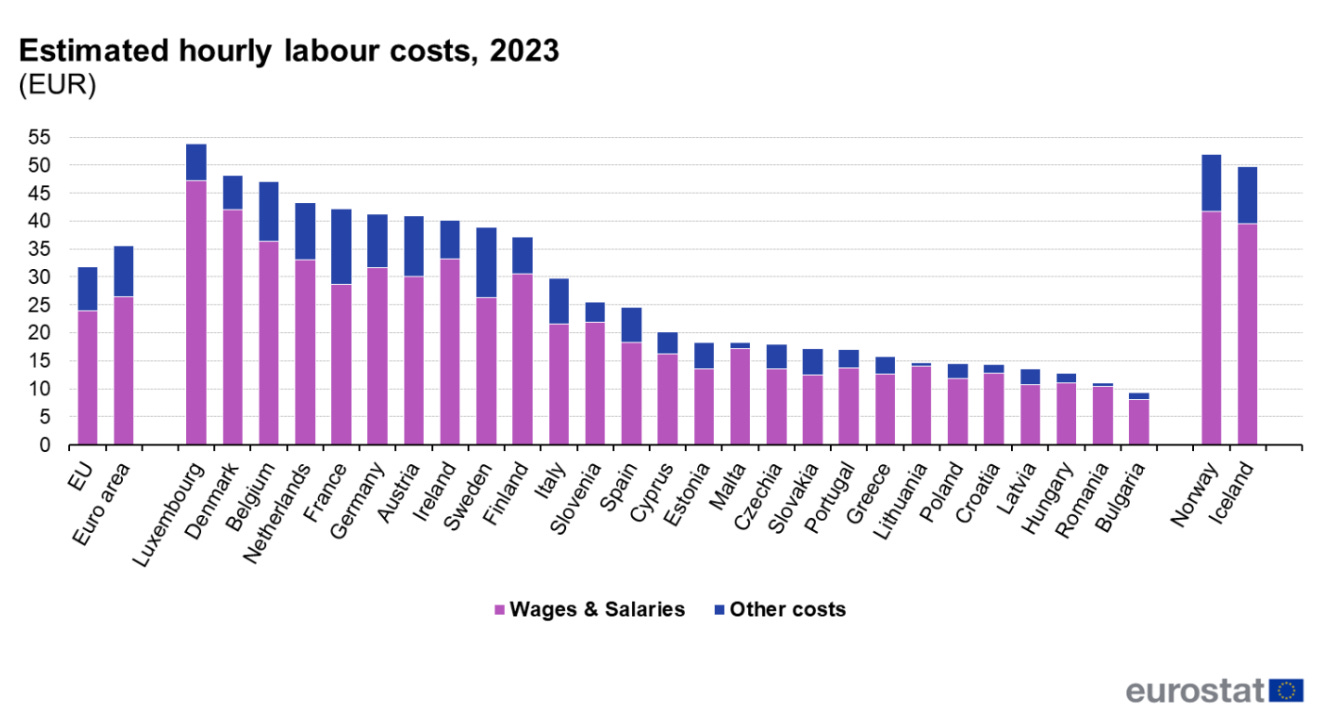

Labour Costs still low

Another way to look at the income level of a country is to analyze its labour costs.

Estimated hourly labour costs in Greece are on the lower end and only look better when compared to parts of Eastern Europe.

Greeks work a lot. In fact, they work more than anyone else in Europe.

But we are not very efficient in the way we work. Our labour productivity is very low compared to OECD and EU/EZ averages. We have a labour productivity deficit.

Simply put, Greeks work more hours but produce less economic value during that time, which means that the actual hourly compensation rate is depressed. If we became more efficient in the way we worked, that number could grow higher.

The impact of tax avoidance

Greece has a very large shadow economy, estimated by Bank of Greece Governor Yannis Stournaras at around 21% of the country’s GDP.

While the Greek tax authorities are today much better at locating offenders, many Greeks still tax evade and avoid declaring their income, either in part or in full.

This is especially common across self-employed workers.

In 2021, plumbers declared an average net salary of €634 per month with 47% of them reporting they were in the red against their expenses. Dentists declared €676 per month (28% in the red). Taxi drivers declared €310 per month (44% in the red).

Anyone with even the slightest understanding of the Greek economy knows that these numbers are all but impossible.

What this means is that the average income in the country is probably significantly higher than the one reported through public statistics.

The gap between Greece’s real consumption per capita and its real GDP per capita is pretty telling: Greeks seem to consume much more than they seemingly produce in official economic terms. Since they are far from the world’s best savers and Greek banks no longer lend easily, where do many Greeks keep finding the money?

Tax avoidance is a big part of the answer.

Conclusion

The financial crisis was brutal and left deep scars in the salary levels of Greece.

At the same time, longer-term trends consistently showed Greece trailing OECD and EU averages, even before the start of the crisis. We were always laggards.

Despite high inflationary pressures continuing to this day, recent increases in the real minimum wage are meaningful and the average income is in fact starting to rise.

To get the full picture, factoring in the effect of tax avoidance is also important.

There is still a long way to go until Greece catches up with its peers. Sadly, families with children are currently hit the hardest. But the country is also making progress.

Next time someone brings up the topic of Greek salaries and either paints it too black or too white, remind them: it’s mostly fifty shades of dark grey.

🏭 Economy & Business

Athens stock exchange best months are April and July

Hospitality investing continues like crazy with many new mega deals

Tourism sector still faces a number of challenges despite growth

Government considers reducing income criteria by 30% in 2025

Salaried employees pay much highest taxes proportionally to rest

New six-day work week law highlighted by Bloomberg

Metlen’s Evangelos Mytilineos gets a profile from The Sunday Times

🤖 Tech & Startups

Newjobs is a new Greek jobs marketplace launched by Workable

We need to 10x the number of entrepreneurs, writes Alex Alexakis

Tax incentives for investments in R&D are being rolled out

Women startup competition taking place at this year’s TIF

National Observatory of Athens is upgrading its telescopes

🙌 Celebrating Greek wins

Greece has so far won 10 medals in the 2024 Paraolympics

Telis Oikonomou (in Memoriam) built one of Greece’s best steakhouses

Lefteris Papadopoulos honored by an immense music concert in Athens

📌 Spotlight: For the festivals (Για τα πανηγύρια)

A month ago, I asked on twitter: “what’s your favorite August festival in Greece?”

This was not a random question. Greek festivals are back in fashion!

Contrary to the past, they are now full of young people dancing, singing and having fun. GenZers love them. There’s now even an app showing you festivals nearby!

This does not make everyone happy. And it also brings in new joiners who might not understand the cultural aspects or behave in the most respectful way.

I personally find this rebirth of tradition spectacular. Festivals bring new life to many of Greece’s smaller villages. And keeping the connection with today’s youth alive is key to making sure they are not forgotten and maybe even grow in the future.

That’s it for this week. I always love hearing from you. Make sure to hit that reply button.

Find me on X or Bluesky for bite-sized opinions.

Until next time!

I liked a lot the subject and your point of view. A deeper read is needed and, if the universe will allow me I will revert. Meanwhile, I am wondering why in some and not in all reports-metrics, Russia and Turkey are tooked in account?

Congratulations on your work - here and in general, from what I'm able to see.

But here is where you go awry. Talking abt the pre-crisis "profligacy":

"...Constant borrowing on a national level, extremely high public sector salaries handed out to partisan ‘clients’ by the Greek political system, as well as various other terrible habits created an unequivocal recipe for disaster."

This is incorrect. When you borrow as a state in your own currency, you cannot default on your state debt unless you want to (for whatever suicidal reason). And Greece, up until 2000, owed in Drachmas, mostly. Now, you are, of course, totally correct about nepotism, corruption, partisanship, etc. Unfortunately, and as it happens, I experienced all that first hand.

But even so, this kind of bad economic policy leads to missing opportunities (to achieve a proper, productive growth, by giving birth to extensive corruption, etc). BUT NOT TO A DEBT CRISIS! Because as a state you owe in the nat'l currency. The solid fact here is that if we, in 2000, had not abandoned our fiscal & monetary independence, i.e. if we had not adopted the Euro as our national currency and bound ourselves by the insane Maastricht limits, we would not have experienced a debt crisis at all.